Earlier this month, a curious piece by Ohio State University psychologist and neuroscientist Gary Wenk appeared in Psychology Today. It purports to explain how “the brain” came to “invent the idea of gods”

Psychology Today has been a mixed bag over the years. I have certainly appreciated Marilyn Mendoza’s sound work on death, dying, and near-death experiences there. That is a topic always at risk of descending into pop science nonsense.

Maybe there is a rule that every so often the descent must be made. Dr. Wenk’s article so much fits the pattern of such articles that its best use is to illustrate their general characteristics.

The pattern begins right up front:

Key points

“When and How Did the Brain First Invent the Idea of Gods?” October 7, 2025 (emphasis added)

- Spirituality may be a specific processing capability that developed following a change in the brain’s wiring.

- This may have happened about 40,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens demonstrated changes in burial practice.

- Changes in specific brain regions may have evolved to encourage altruistic behaviors that benefit others.

The emphasis is added above to illustrate that there are hardly any concrete findings here; just a passionate embrace of the power of “maybe” — that is, speculations based on chosen events. This is not science and is not a good look for a psychology that purports to have some relationship with science.

The Chasm Where Lurks the Unfound

Pointing to some specific pieces of paleontological evidence like drawings and burial customs, Wenk traces key events to an alleged change in human brains about 40,000 years ago:

Paleontological evidence indicates that this human revolution of creating religious artifacts likely occurred within a time frame of only tens of thousands of years. This implies that the changes occurred extremely fast on the scale of evolution. If true, this implies the de novo evolution of new spirituality-specific brain areas could not have emerged; rather, such a fast change suggests that existing brain structures must have shifted their function.

“Brain First Invent”

The vast majority of human beings have lived and died while leaving no trace whatever. Even if they had all left stuff behind, we can’t possibly know anything about vanished human brains. Every so often, paleontologists win the geological lottery, so to speak, and turn up a graveyard, artifacts, or cave drawings. But did these customs and skills only start to happen 40,000 years ago or is that what we have found so far?

As a cautionary tale, I would point to the bombshell discovery of Neanderthal art in 2012. The surviving art was there all the time but its “unfound” status sparked many theories of the inferiority of Neanderthal minds.

The Neuroscience of the “May Haves”

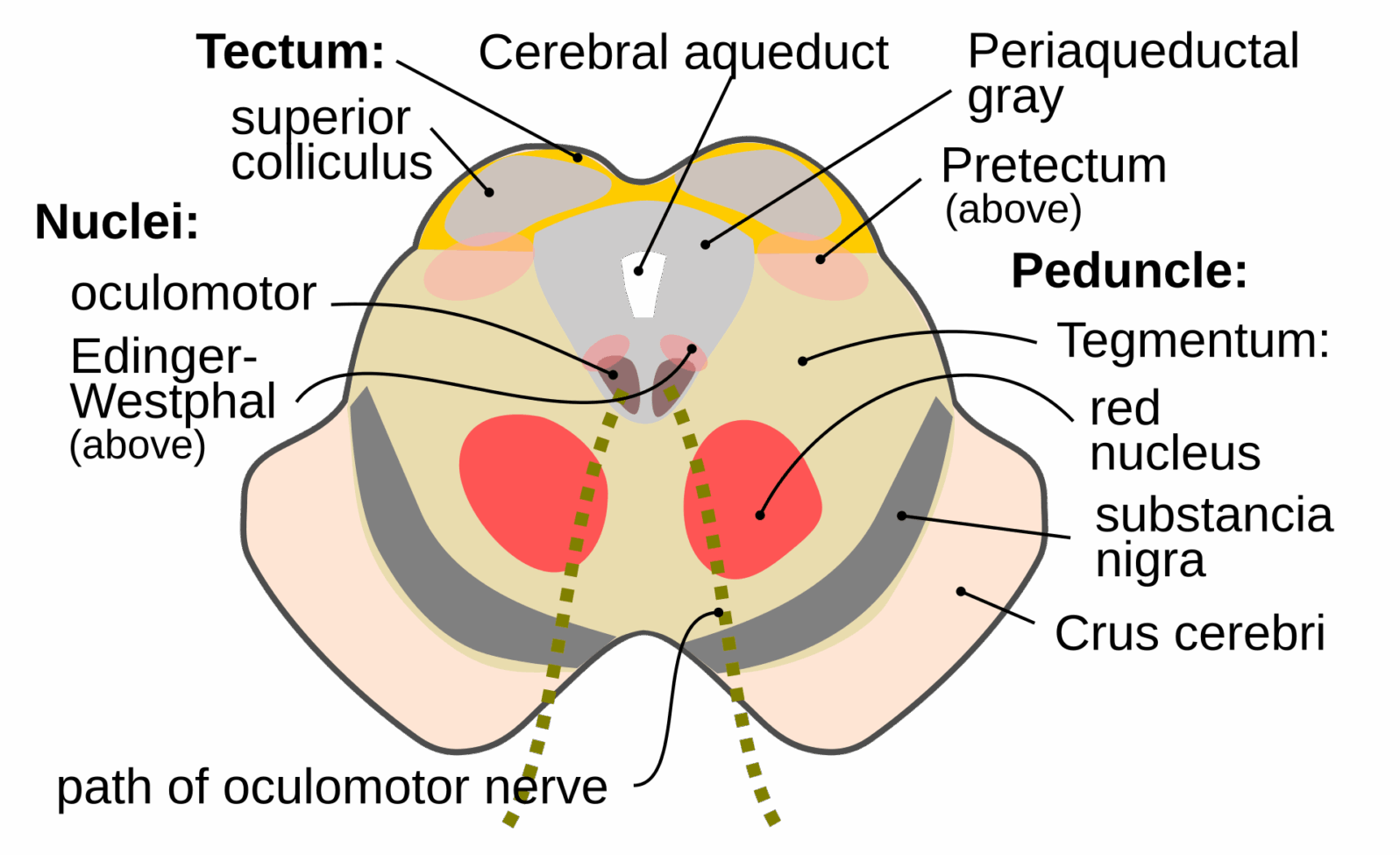

Wenk offers a theory that a brain stem region called the periaqueductal gray plays a role:

Another study mapped spirituality to a specific human brain circuit. The study discovered that self-reported spirituality or religiosity mapped to a brain circuit that was centered on a brain region called the periaqueductal gray. This is quite a fascinating discovery, given that the periaqueductal gray is found in the brain stem, not the cortex, as might be expected from other studies. The periaqueductal gray is an ancient structure believed to play a role in our response to fear, pain, and altruistic behavior. This brain circuit, and the apparent importance of the periaqueductal gray, may have evolved to encourage altruistic behaviors that benefit others in an extended family as well as to reduce the fear of living in the dangerous and unpredictable world of the Paleolithic.

“Brain First Invent”

Maybe. But the brain stem is not a specifically human part of the brain; its relevance to human concerns and activities is not obvious and Wenk does not address that.

Where the Presumption of Atheism Misleads

Because Wenk mentioned neuroscience, I asked for a reaction from neurosurgeon Michael Egnor, first author of The Immortal Mind: (2025). He offered a telling observation: “I note that they never attribute belief in evolution or atheism to an evolved trait. Those things are always considered true in themselves.”

Yes, that’s the famous presumption of atheism at work:

In his influential essay “The Presumption of Atheism,” British philosopher Antony Flew challenges the burden of proof in discussions about the existence of God. Flew argues that the default position in debates on the existence of God should be atheism, as it is the position that does not make any positive claims. In this essay, we will explore Flew’s key arguments and the implications of his approach to the presumption of atheism.

Philo-Notes, July 7, 2023

One effect of the presumption is that all kinds of nonsense can be grandfathered by atheism as reasonable scientific thinking. Meanwhile, all evidence that points in any other direction comes under hostile scrutiny.

Incidentally, near the end of his life, Antony Flew (1923–2010) renounced atheism and became a deist (he then believed in God though not in any specific conception of God). He even wrote a book, There Is a God (HarperOne 2008). But, of course, in high school science classes and science mags across the spectrum, the damage was done.

About the brain inventing gods, Egnor adds, “Hopefully the day will come soon when pseudoscience like this will be laughed at rather than taken seriously.” Yes. And the hour is late.

Cross-posed at Mind Matters News.