On ID the Future, I recently interviewed Rabbis Elie Feder and Aaron Zimmer about an episode of their podcast Physics to God, in which they explain how the laws of nature point to evidence of design beyond the standard fine-tuning argument. They also summarized another episode in which they highlight the extraordinary lengths some physicists go to avoid acknowledging the design implications. The interview continued our discussion from a previous podcast, in which they described the failure of multiverse theories to account for the evidence of design without an actual designer.

Beyond Fine-Tuning

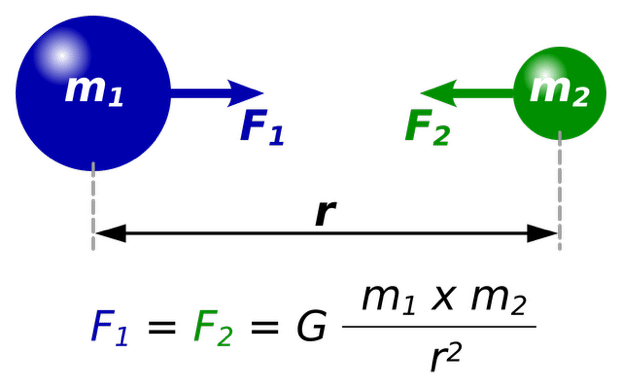

The standard argument for design in the laws of physics centers on the fine-tuning of fundamental constants. Consider the law of universal gravitation (Figure 1): the force between two masses is given by the gravitational constant (G) multiplied by the product of the masses (m₁ × m₂) and divided by the square of the distance between them (r²). The fundamental constant G determines the relative strength of the force; a larger G corresponds to a stronger attraction. In principle, its value could have been vastly smaller or larger than its actual value. Yet life-permitting conditions arise only if G falls within an exceedingly narrow range, far smaller than the full range of possible values. The fact that this constant resides in the seemingly improbable range that allows for life points to the laws having been designed by a superintellect for that purpose. The same holds true for many other constants and for our universe’s initial conditions. Many have forcefully presented this argument for the design behind our universe (here, here, here).

In the first part of our interview, Feder and Zimmer took the argument even further by focusing on the qualitative nature of the laws, which is their general form or structure. The form of the law of universal gravitation is the product of masses divided by the distance raised to the power of 2. Yet the law’s mathematical structure could have been very different, such as the masses being added rather than multiplied, or the distance raised to a power greater than 2. In the case of gravity, the law’s structure is not surprising, but other laws have forms that are entirely unexpected.

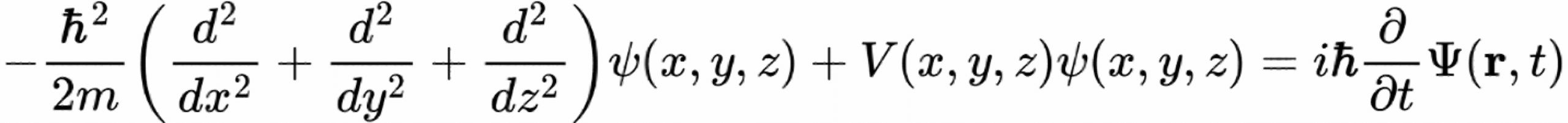

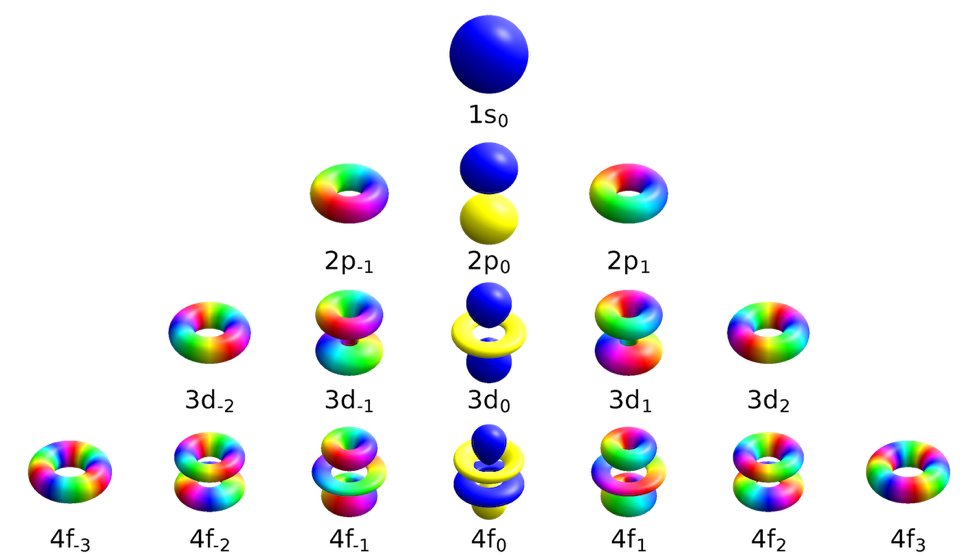

One of the fundamental laws governing quantum mechanics is expressed by Schrödinger’s equation (Figure 2). In atoms, it determines the electrons’ orbitals, which represent the probability distribution of their locations around the nucleus (Figure 3). The equation includes second-order spatial derivatives (x, y, and z), a first-order time derivative, and an imaginary number (i). No one would have expected an equation governing the real world to have an imaginary term. Yet this exact form is essential for the existence of orbitals, which enable the chemistry that supports life.

Many other qualitative features of the physical laws are essential for a life-permitting universe. Gravity must be long-range, relatively weak, and cumulative — meaning its strength increases with mass, allowing stars and planets to form. By contrast, the electromagnetic force must be far stronger than gravity, long-range, but noncumulative — positive and negative charges cancel one another, preventing electromagnetic forces from overwhelming gravity on planetary scales. In addition, the strong nuclear force must be the strongest of the fundamental forces to bind protons and neutrons together in nuclei. Yet it must also be extremely short-ranged; otherwise, it would turn galaxies into a single massive nucleus. Many additional examples illustrate similar life-critical requirements. The likelihood is beyond remote that a set of physical laws represented by equations with random mathematical structures would correspond to a life-friendly universe, regardless of the choice of fundamental constants.

Attempts to Explain the Evidence

Many physicists have sought to explain this evidence while remaining within a strictly materialistic framework. One early effort was the quest for a “theory of everything,” a single, ultimate law of nature that would show the laws governing our universe had to be the way they are. Most physicists came to realize that no such law could exist since many sets of self-consistent laws are possible. In response to this conclusion, physicist Max Tegmark offered the most radical proposal: every self-consistent set of laws corresponds to an existing universe. The set of laws governing our universe and universes with every other set of life-permitting laws had to exist out of logical necessity.

Feder and Zimmer quote Tegmark describing what he terms the mathematical universe:

If the Theory of Everything…exists and is one day discovered, then an embarrassing question remains, as emphasized by John Archibald Wheeler: Why these particular equations, not others? Could there really be a fundamental, unexplained ontological asymmetry built into the very heart of reality, splitting mathematical structures into two classes, those with and without physical existence? After all, a mathematical structure is not “created” and doesn’t exist “somewhere”. It just exists. As a way out of this philosophical conundrum, I have suggested that complete mathematical democracy holds: that mathematical existence and physical existence are equivalent, so that all mathematical structures have the same ontological status.

Failure of the Mathematical Universe

In the second part of our interview, Feder and Zimmer explained why Tegmark’s proposal collapses for two reasons. First, it conflates mathematical existence with physical existence. The fact that a set of self-consistent mathematical laws can be formulated does not mean that a universe governed by those laws actually exists. Most mathematically coherent sets of equations are never instantiated in the physical world; they remain abstract possibilities rather than realized actualities.

Second, the proposal faces the meta-measure problem. The only concrete prediction of an expansive multiverse is that our universe should be typical. In other words, based on some sensible criterion or measure, our universe should represent the type of universe that should be relatively common. As an analogy, lottery numbers that win grand prizes should typically be random. They should not correspond to the social security number of a winner’s close friend or family member. In the mathematical universe, the most common universes that support life, under the Typical Universe Premise, should have the most complex set of physical laws; there are many more possibilities for constructing laws with more terms. Our universe appears to be the opposite. The laws are few, simple, and elegant.

As Feder and Zimmer explained in our previous podcast, physicists have sought a realistic measure to classify ours as typical, but they have failed. Even more problematic, the mathematical universe predicts that every possible measure should exist, so one can never justify the Simple Universe Premise applying to our universe. The only way to explain why our universe is governed by such simple and elegant laws that support life is that a mind chose life-permitting laws that are sufficiently simple that we could discover them and advance scientifically.