The attribute of the human mind that allows us to realize (grasp, apprehend, perceive, or understand) something as true, even if the concept is abstract and unprovable by logical deductions, illuminates an immaterial nature of our being. The new book, The Immortal Mind, by Dr. Michael Egnor and Denyse O’Leary powerfully argues for this conclusion based on modern neuroscientific evidence demonstrating that the human mind is more than the brain.

The Medieval Model

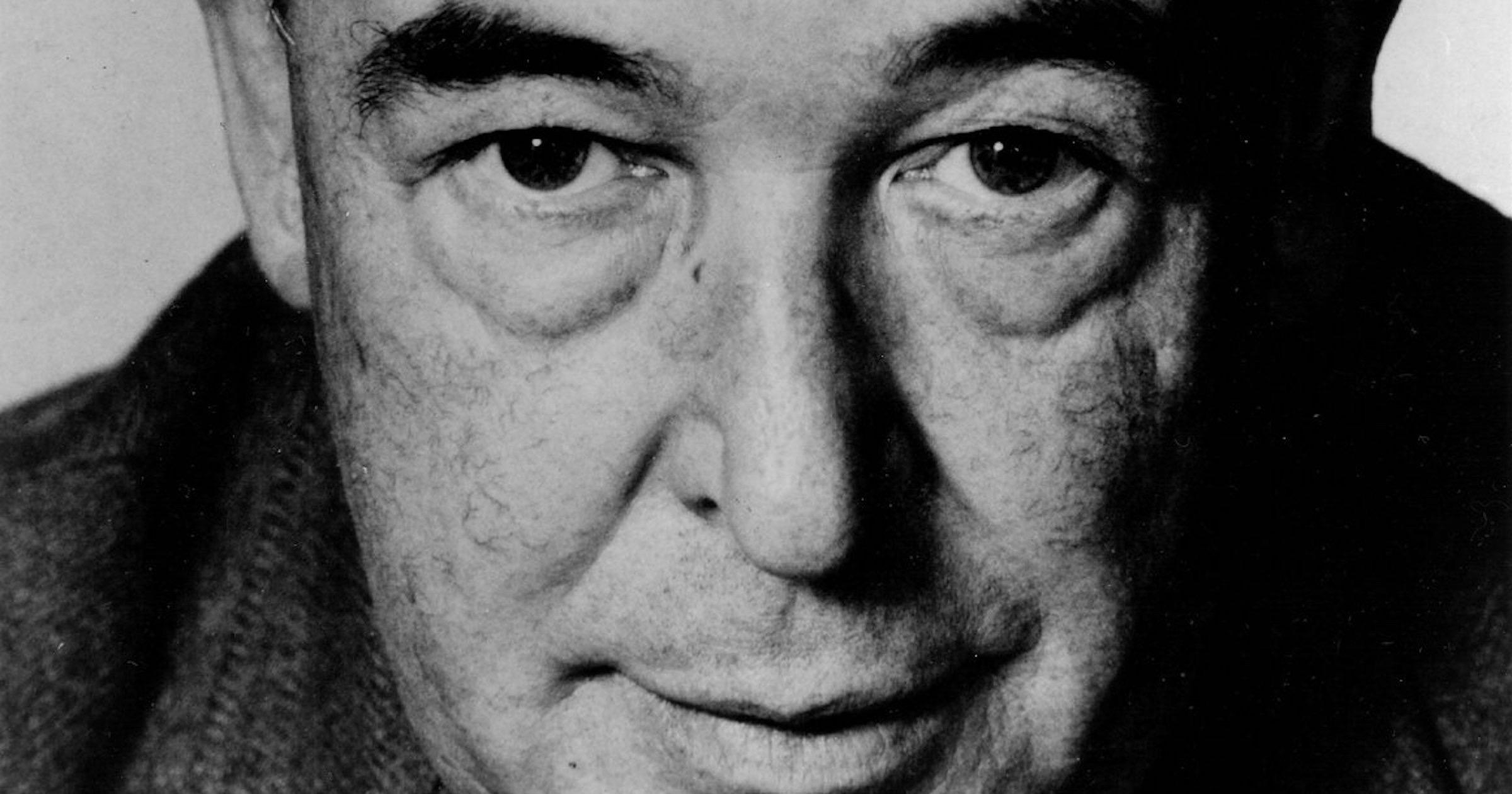

Classical and medieval scholars would not be surprised at the mounting scientific evidence for the immaterial soul, except perhaps that such a conclusion should be considered novel. C. S. Lewis, in his lectures on the Medieval Model of reality, summarizes an earlier understanding of three levels of immortal souls.1

Rational Soul, which gives man his peculiar position, is not the only kind of soul. There are also Sensitive Soul and Vegetable Soul.

Lewis elaborates on the medieval view that admits these three types of immaterial souls.

The powers of Vegetable Soul are nutrition, growth and propagation. It alone is present in plants. Sensitive Soul, which we find in animals, has these powers but has sentience in addition….All three kinds of soul are immaterial. The soul — as we should say, the ‘life’ — of a tree or herb is not a part of it which could be found by dissection; nor is a man’s Rational Soul in that sense a ‘part’ of the man.2

Although discerning three different types of souls, the medieval philosopher would hold that the higher form of a soul includes the lower forms. A human being’s rational soul incorporates aspects of the sentient soul and the vegetable soul. Humans are more than animals, but share some characteristics with them; animals are more than vegetables, although sharing some physical attributes with them.

I find it fascinating that modern research in biology seems to be guiding the academy, albeit reluctantly, toward the view that even single-celled organisms and plants exhibit an immaterial life, sentience, or soul. Richard Sternberg’s work supports even an immateriality of the cellular genome, invoking Platonic forms.

C. S. Lewis’s Exposition

With the modern scientific view veering towards acknowledgment of an immaterial soul, it will be beneficial to further consider the subtleties of this concept in Lewis’s exposition of the soul from classical and medieval scholars. We can recognize that the rational soul of humans exercises two faculties, Intellectus and Ratio, which may be associated with insight (or realization) and deductive reasoning. Lewis cites Aquinas’ explanation of these two aspects of the human rational soul:

intellect (intelligere) is the simple (i.e. indivisible, uncompounded) grasp of an intelligible truth, whereas reasoning (ratiocinari) is the progression towards an intelligible truth by going from one understood (intellecto) point to another.3

In Lewis’s words,

We are enjoying intellectus when we ‘just see’ a self-evident truth; we are exercising ratio when we proceed step by step to prove a truth which is not self-evident.4

Lewis elaborates that human intellectus is a “clouded intelligence,” which in the medieval view is “enjoyed in its perfection by angels.” The human cognitive experience includes flashes of insight, capturing truths of reality in a moment of brilliance, but we more often than not proceed upward towards truth by the stepwise process of reasoned thought. But even if a ladder is used to allow a person to climb higher than one’s head, the bottom rung still needs to rest on a solid foundation. As Lewis insightfully observes,5

…for nothing can be proved if nothing is self-evident.

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

This off-handed assertion by Lewis is a profound, parallel conclusion to the essence of mathematician Kurt Gödel’s assiduously proven Incompleteness Theorems.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems allow and even demand that within the physical reality of this universe there exist truths that cannot be derived from physical reality. Gödel realized that these truths include the immaterial aspect of the human mind and the immortal nature of the human soul.

The context of Lewis’s statement above is that without realizations of unprovable foundational truths, any attempt at reaching a logically defensible conclusion is impossible. If this applies to human thought, it cannot help but apply to models of artificial intelligence (AI). That AI cannot attain anything like a “realization” (a non-derived insight of truth) is self-evident; therefore, AI cannot truly think.

From Nature or Beyond Nature

From where do humans acquire our unique, immaterial souls? Only two options present themselves: either from nature, or from something beyond nature. That nonliving matter cannot give rise to a living being, let alone an immaterial mind, is a truth that many believe self-evident. A stepwise natural process leading from disorganized atoms to a living, conscious physical being is certainly counter-indicated by the laws of nature.

To ascribe our rational minds to an irrational source, or to suggest that we acquired our personhood from impersonal matter or forces, is arguably a self-evident absurdity. Pressing a similar point regarding the source of human free will, Dr. Egnor draws this conclusion:

Intellect and will are immaterial powers of the mind. The will is not determined by matter, and free will is real.

In a recent article, philosopher J. P. Moreland finds agreement with classical thinkers on the immateriality of the human soul.

In the end, Moreland argues that the best explanation of who we are is that we are souls — immaterial, unified beings that give order and purpose to our physical bodies. This classical view, supported by both Aristotle and later thinkers, offers a clearer and more complete understanding of the human person than physicalism or any form of materialism ever can.

As humans, although our perception of truth may be shadowed and limited, we will only grow in our understanding by embracing what is self-evident and not denying the light we’ve been given.

Notes

- C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1964, 2013), 153.

- Lewis, The Discarded Image, 154.

- Lewis, The Discarded Image, 157.

- Lewis, The Discarded Image, 157.

- Lewis, The Discarded Image, 157.