Needless to say, human mothers have been giving birth to sons and daughters as long as there has been human reproduction. But it is only in the last few decades that medical science has been able to unravel what is going on at the molecular level within the uterus during labor and delivery.

Now, a recent study in Science reports on how “PIEZO channels link mechanical forces to uterine contractions in parturition.” It’s nicely explained at Science Daily, which says the study has propelled our understanding to a new level that “could one day lead to better ways to manage childbirth.”

From “Scientists discover how the uterus knows when to push during childbirth,” with my commentary:

Childbirth depends not just on hormones, but on the uterus’s ability to sense physical force. Scientists found that pressure and stretch sensors in the uterine muscle (PIEZO1) and surrounding nerves (PIEZO2) work together to trigger coordinated contractions. When these sensors are disrupted, contractions weaken and delivery slows.

Here is an opportunity to wonder if these findings are best explained by precision design logic or undirected Darwinism.

Two Problems

Successful childbirth depends on the uterus producing steady well-organized contractions that move the baby safely through delivery.

Just because there is smooth muscle in the uterine wall does not automatically mean that there will be coordinated, well-organized muscle contraction during labor, resulting in a safe delivery.

The same can be said for heart muscle. In that context, when things are working properly, steady, well-controlled, coordinated ventricular contractions result in enough blood being pumped throughout the body.

A common cause of sudden death is ventricular fibrillation. This is when contractions of the ventricular muscle are totally disorganized, resulting in chaotic, rapid, and uncoordinated quivering. In that scenario, the heart is unable to pump enough blood throughout the body and death takes place very quickly.

So too, totally disorganized uterine muscle contraction would prevent proper labor and delivery.

How does the body make sure that this does not happen when it is time for the baby to be born?

Hormones such as progesterone and oxytocin play a major role in controlling this process. For years, however, researchers have also suspected that physical forces involved in pregnancy and birth, including stretching and pressure, contribute in important ways.

Progesterone and oxytocin are two dominant hormones for the yin (restful) and yang (active) phases of uterine muscle during pregnancy.

Progesterone (yin), through specific receptors in the uterine muscle, keeps the muscle relaxed through most of pregnancy. However, as term approaches, even though progesterone levels remain high, for various reasons, the uterine muscle starts to become less responsive to progesterone’s usually calming effects. That makes it easier to become activated and more likely to contract.

In contrast, oxytocin (yang), through specific receptors in the uterine muscle, stimulates the muscle to contract. As term approaches, certain hormonal changes, along with more stretching of the cervix and pelvic floor, result in more oxytocin being released from the pituitary and the formation of more oxytocin receptors within the uterine muscle.

The progressive decrease of progesterone-induced relaxation with the simultaneous increase in oxytocin-induced stimulation, as term approaches, results in the uterine muscle flipping from the “quiet phase” it enjoyed during most of pregnancy, to the “contractile phase,” aka labor.

Since the time of Darwin, medical scientists have suspected that uterine stretching and pressure directly affect labor. Many decades before the knowledge of hormones, scientists noticed that a distended uterus contracts more strongly. They also noticed that more than one fetus in the uterus increases the risk of preterm labor, and mechanical pressure on the cervix accelerates labor.

In addition, modern research and clinical experience with, for example, premature and stalled labor resulted in medical scientists concluding that the complex hormone system alone could not fully explain the precise timing, coordination, and strength of uterine muscle contractions for childbirth.

How does the uterus “know” when it needs to power up and synchronize thousands of individual muscle cells to act as a single unit and push during delivery?

PIEZO1 and PIEZO2

As the fetus grows, the uterus expands dramatically, and those physical forces reach their peak during delivery, says senior author Ardem Patapoutian. “Our study shows that the body relies on special pressure sensors to interpret these cues and translate them into coordinated muscle activity.” These sensors are ion channels built from proteins known as PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 which enable cells to respond to mechanical force.

Dr. Patapoutian shared the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his Scripps Research team’s discovery of PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 in 2010. This explained the biological mystery of how cells convert physical pressure into electrical signals, a process called mechanotransduction.

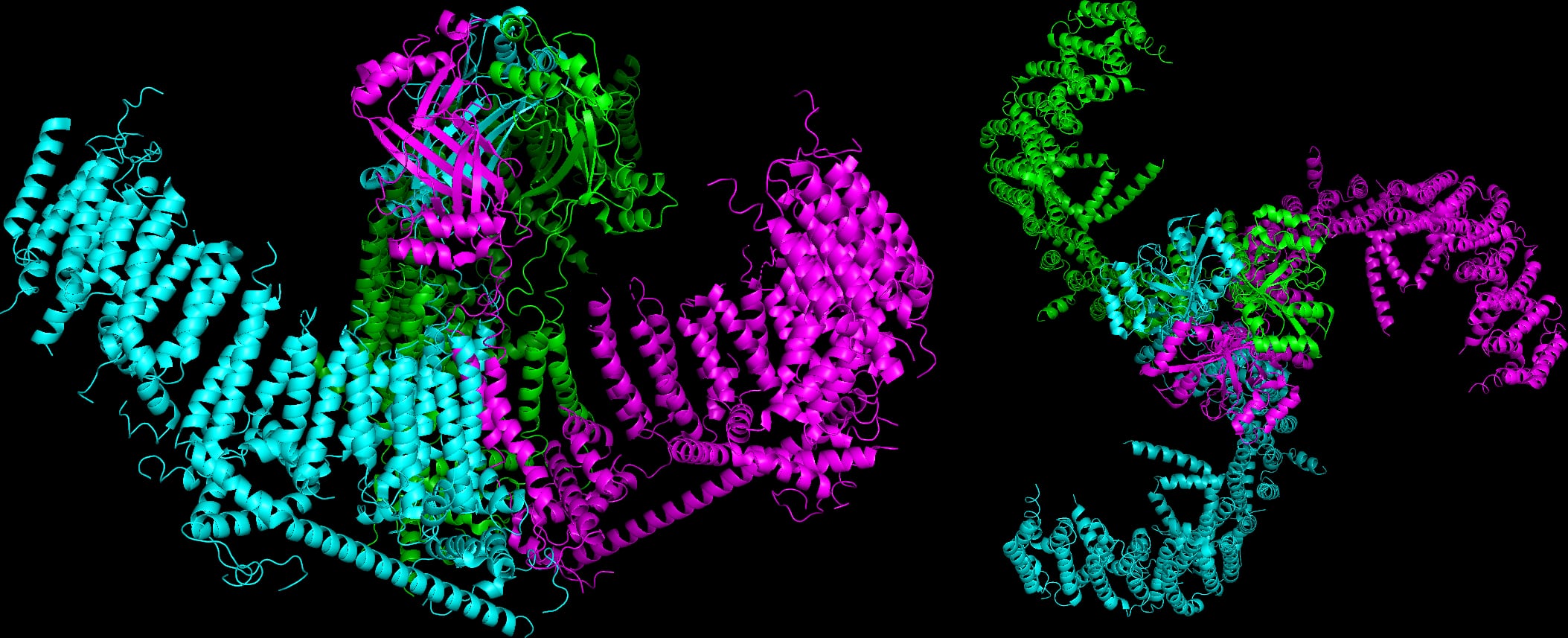

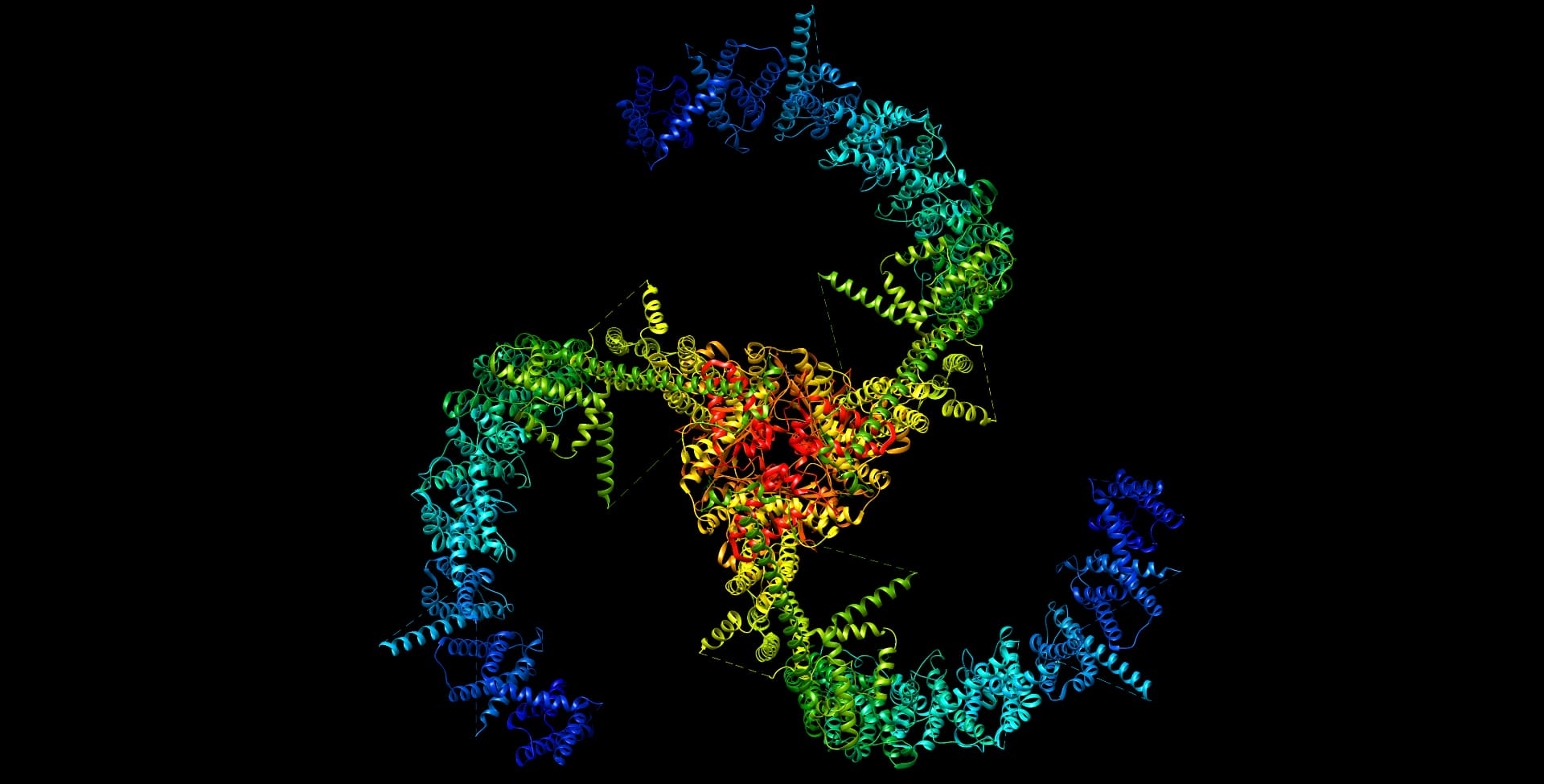

PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 are large (more than 2,500 amino acids) three-bladed, propeller-shaped transmembrane proteins with a central (ionic) pore at the hub. Activation of the molecular propellers, by mechanical tension on the cell membrane, opens the central pore to let calcium ions flood into the cell. This leads to downstream signaling pathways that cause a change in function.

PIEZO1 is expressed in many non-sensory tissues, where it plays a critical role in detecting sheer stress and pressure. It is present in red blood cells for volume control, bone cells for skeletal remodeling, endothelial cells for vascular development, skin cells for wound healing, and kidney cells for urine production, to give just a few examples.

PIEZO2 has a more specialized role. It is present in sensory nerve cells that allow the nervous system to feel what is going on inside and outside the body through touch, vibration, gentle pressure, and stretch. The cells detect muscle stretch and joint position (proprioception), affording coordinated movement, balance, posture, and, through Merkel cells in the skin, fine touch discrimination.

In the new study, researchers found that PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 perform separate but complementary tasks during labor. PIEZO1 operates primarily within the smooth muscle of the uterus, where it detects rising pressure as contractions strengthen. PIEZO2, in contrast, is located in sensory nerves in the cervix and vagina. It becomes activated as the baby stretches these tissues, triggering a neural reflex that boosts uterine contractions. Together, these sensors convert stretch and pressure into electrical and chemical signals that help synchronize contractions.

PIEZO2 mainly contributes to the sensory side of childbirth. It informs the brain about what the uterus and birth canal are experiencing. Some of this sensory information feeds back and “boosts uterine contractions.” But it mostly contributes to maternal pushing, which culminates in the fetal ejection reflex. In contrast, PIEZO1 is involved in turning up the amplitude and coordinating more frequent uterine muscle contractions to make sure childbirth takes place. It does this mostly by increasing the number of oxytocin receptors, releasing other biomolecules, and, in particular, synchronizing uterine muscle contraction by increasing the expression of connexin 43 (Cx 43). What’s that?

Connexin 43 (Cx43)

Further investigation revealed that PIEZO activity helps regulate levels of connexin 43, a protein that forms gap junctions. These microscopic channels connect neighboring smooth muscle cells so they contract together rather than independently.

For individual cells, multicellular life is like riding the subway during rush hour. They can’t help bumping up against each other. Depending on the tissue, this gives neighboring cells the opportunity to stick together, communicate, and coordinate their behavior.

For example, cells in the lining of the intestine have tight junctions that seal most of their borders from each other, while cells in the skin have spot junctions that are more like rivets. In contrast, gap junctions, in heart and smooth muscle cells, are nano-sized channels that let ions and biomolecules move between them. This allows electrical coupling and coordinated contraction.

Although gap junctions within the uterine (and heart) muscle were noted on electron microscopy in the early 1970s, it wasn’t until a few decades later that molecular biologists identified them as transmembrane proteins which they named connexin 43 (Cx43). It is the expression of Cx43 gap junctions within the uterine muscle that plays a critical role in the synchronized contraction of the uterus during labor and delivery.

There are many factors that can turn the expression of Cx43 gap junctions either on or off. For uterine muscle, progesterone is the dominant hormone that turns off the expression of Cx43 gap junctions, generally preventing labor from developing during most of pregnancy. In contrast, oxytocin, and the stimulation of the PIEZO1 receptors within the uterine muscle due to increased stretching and pressure during labor, turns on the expression Cx43 gap junctions.

As labor progresses, the increasing effects of oxytocin and PIEZO1 stimulation override the diminishing effects of progesterone, resulting in an increase in Cx43 expression and uterine muscle synchronization to bring about childbirth.

Delivering the Goods

“Childbirth is a process where coordination and timing are everything,” says Patapoutian. “We’re now starting to understand how the uterus acts as both a muscle and a metronome to ensure that labor follows the body’s own rhythm.”

As fetal growth and uterine distension maximize toward the end of pregnancy, the associated diminished effects of progesterone, with the simultaneous increased effects of oxytocin, trigger the beginning and early progression of labor. However, this just sets the stage for what is really needed to accomplish delivery. For as every mother can tell you, at some point in the birthing process the frequency and amplitude of uterine contractions increase dramatically.

This is now known to be due the steady increase in stimulation of PIEZO1 stretch and pressure receptors within the uterine muscle cells as labor progresses. This causes them to increase their expression of Cx43 gap junctions, resulting in synchronization and the increase in frequency and amplitude of uterine muscle contraction. These, with the effects of PIEZO2 stimulation from the lower reproductive tract, are what is needed to make sure that labor is effective enough to bring about childbirth.

Childbirth requires that all the right parts be in the right places and optimally fine-tuned so that the uterine muscle remains relaxed throughout pregnancy until it realizes that it is time to deliver the goods.

Logic of the Investigative Process

Let’s review the investigative process that led to what we know now. In Darwin’s time, physicians (and mothers) knew from experience that increased stretching of, and pressure within, the uterus ultimately increases the force of contraction. But how does that happen?

Many decades later, medical science discovered hormones like progesterone and oxytocin, along with their specific receptors in the uterine muscle, the counterbalancing (push-pull) effects of which were determined to be related to the onset of labor. But that’s not the whole story.

A few decades ago, gap junctions like connexin 43 were discovered to be the mechanism by which heart and smooth muscle cells (like that in the uterus) become synchronized to effect coordinated contraction. That is absolutely necessary for these organs to have the functional capacity to do what they are supposed to do. But how could the uterine muscle stay relaxed throughout pregnancy and then with, full fetal development, transition to being activated enough for childbirth?

In the last few years, medical scientists discovered there are mechanoreceptors (PIEZO1 and PIEZO2) within the cells of various tissues that can detect stretch and pressure. Maybe these receptors are also in the uterine muscle? That could explain how as pregnancy nears its endpoint, the uterus can adapt appropriately to the changing situation at the right time.

Do you think the investigative process assumed the system allowing for childbirth came into being by an undirected, blind, and clunky process like Darwinism? Does it make sense to use reverse engineering to figure out such a finely tuned, precision operation that is vital for life, and then assume that a mind was not behind it all?

In a recent article here, Dr. Emily Reeves compared intelligent design to systems biology. She called the two a “natural fit”:

Attempts to reconcile systems biology’s top-down reality with the bottom-up nature of Darwinian evolution always feel a bit forced. For example, I’ve not seen serious investigation of the waiting times required to achieve the top-down design of even a simple system. There is no consideration of how many single-step mutations would be necessary, nor any estimates of the amount of coordination required. I think this is because the problem is actually too hard.

Actually, it’s impossible. In the example we’ve been discussing, Darwinian scientists will tell you that progesterone and oxytocin, along with their specific receptors, PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 and connexin 43, all emerged through selective pressure, being then conserved over time. But this does not address how each of these parts fits into a coherent system that demonstrates finely tuned precision, resulting in a process vital for survival.

As Dr. Marcos Eberlin wrote in his book Foresight: How the Chemistry of Life Reveals Planning and Purpose, “If Nobel-caliber intelligence was required to figure out how this existing engineering marvel works, what was required to invent it in the first place?” That question is wisdom to live by.