Editor’s note: Welcome to a Science and Culture Today tradition: a countdown of our Top 10 favorite stories of the past year, concluding on New Year’s Day. This article was originally published on October 22, 2025. Our staff are enjoying the holidays, as we hope that you are, too! Help keep the daily voice of intelligent design going strong. Please give whatever you can to support the Center for Science and Culture now!

You can’t be good at everything. There are trade-offs. For example, a race car has advantages in the environment of a racetrack, but a jeep has advantages in the environment of a muddy, rocky road. Just as a car can be designed for speed on a racetrack or for off-roading, there are design trade-offs in biology. Understanding these trade-offs and their optimization for populations is key to understanding examples, often reported by science media, of “evolution happening before our eyes.”

Key Connections between Trade-Offs and Optimality

Trade-offs are necessary in multi-objective optimality. In other words, a system must be optimized over multiple variables, entailing trade-offs between separate objectives. Trade-offs are fundamentally connected to optimality because they define the constraints within which a system must operate to achieve the best possible performance. In both engineering and biology, achieving an optimal solution often means balancing competing objectives rather than maximizing or minimizing a single variable such as speed.

Whether a design is optimal, then, depends on the tasks to be performed. Think again about the car example. If you put a race car onto a rocky, winding road up to an old mining town, it is going to have very low “fitness.” Put a jeep on the same road and it will have high “fitness,” because its design is matched to the tasks at hand. Thus, optimality is contingent on the environment the object or organism is placed within. Or I could say optimality is dependent upon the objectives for which the designer is optimizing it.

An Introduction to Performance Space, and Pareto-Optimality

I’m basing much of the following discussion on systems biologist Uri Alon’s work (Alon 2019; Shoval et al. 2012). Let’s imagine that we are designing cars: a jeep and a race car. The two performance features we are interested in are acceleration and the ability to cross rough terrain. If we plot performance 1 on the x-axis and performance 2 on the y-axis, then we can map any design onto this performance space (Figure 1). Designs that are bad at both goals are obviously not considered. Instead, consideration is given to designs that excel either in acceleration and maximum velocity or in traversing rough terrain — or that strike a balance between the two. This leads to a Pareto front, an engineering term (in honor of Italian engineer Vilfredo Pareto) defined as the set of designs where no single option can be improved in all aspects simultaneously. If a continuous range of vehicles exists along this Pareto front, drivers will select different models based on their specific needs.

A design or phenotype that is maximally optimized for one trait, such as we see at point A in Figure 1, which is maximized for Performance 1 (acceleration), is called an “archetype.”

Reverse Engineering to Find Optimization Criteria in Biology

Much as in human engineering, we also find that biological systems face trade-offs. For instance, a famous example of “evolution,” the 17-“species” finch radiation on the Galápagos Islands, is an example of a population moving along a Pareto front. Peter and Rosemary Grant collected data from 1972 to 2001 on “natural selection” by measuring five variables of the medium ground finch and cactus finch in the Galápagos (Grant and Rosemary Grant 2002). This data was then analyzed using a reverse engineering approach where the finch phenotypes were quantified in trait space. Trait space is represented by having one trait on the x-axis and one on the y-axis, so it is similar to performance space.

Here’s how Uri Alon describes this reverse engineering:

We simply plot the data in trait space, using all the traits that we can measure. The axes are the traits, and each phenotype is a point in this space. For example, each beak is a point in a space of traits such as beak width, depth, curvature, and so on. (Alon 2019)

Once plotted in trait space, the data will take on a shape (line, triangle, polytope), and that shape can help us figure out how many traits are being optimized and even what those traits might be. This works because optimization according to tasks creates particular geometric shapes in trait space. If one plots trait data and sees a curve, then two tasks are being optimized. If one sees a curvy triangle, then three traits are being optimized. If you see a curvy tetrahedron, four traits are being optimized. At the vertices of the lines lie the archetypes or specialists. Designs in between the vertices are generalists; they are not the best at doing any particular task. Yet they can perform multiple tasks with some proficiency, which can also be advantageous. From looking at what the organisms closest to the vertices do really well, the tasks being optimized can be inferred.

Trade-offs for Darwin’s Finches

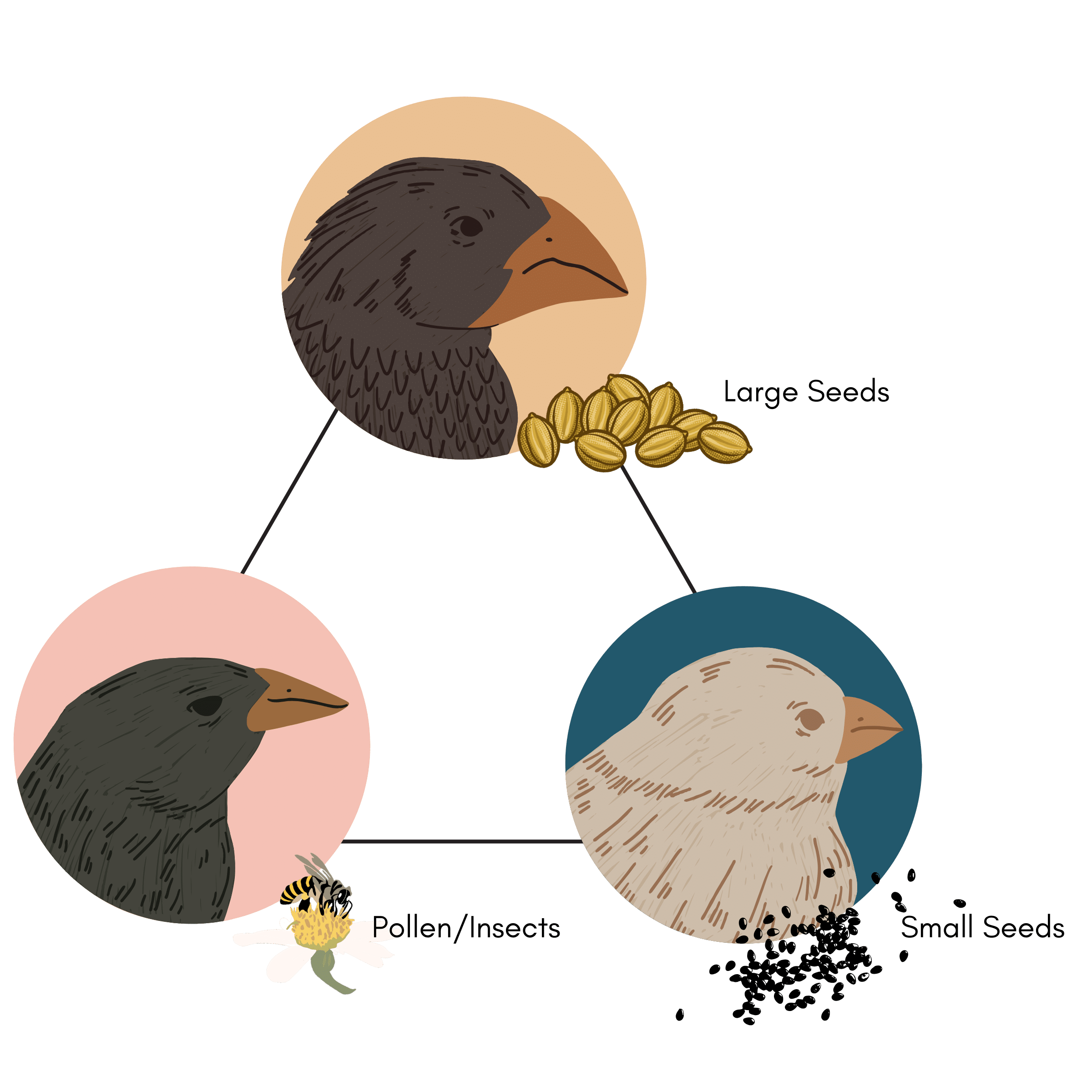

On Daphne Major, a Galápagos island, there are three major types of finch food: large seeds, small seeds, and pollen and insects. Some finches are optimal for eating just large seeds; these finches have a large beak and a large body size (Figure 2). Let’s call this the Large Seed Archetype. Other finches are optimal for eating small seeds; these finches have a small stubby beak and a small body size. We can call this the Small Seed Archetype. Other finches are optimal for eating the pollen and insects; these finches have a straight, pointy beak and a medium body size. And let’s name that one the Pollen/Insect Archetype. Each archetype is a specialist or the very best at a particular task. The finch that is optimized for eating large seeds is, by definition, not optimal for eating small seeds due to the trade-offs between these two tasks (you can’t have a hooked short beak and a long skinny beak at the same time). Finch populations can move amongst these archetypes based on environmental conditions.

Pre-Existing Genetic Potential Over Random Novelty

As species move along the pareto front, biologists say the species are “evolving before our eyes.” They often reach the conclusion that this is an example of random mutation and natural selection creating novelty. Yet, beyond the fact that such directed movement contradicts the hypothesis of randomness, a closer examination reveals that the genetic capacity for this Pareto trajectory already exists prior to any selective pressures. If that capacity existed before evolution got its start, then nothing truly “novel” has evolved.

To understand the molecular basis for the finch radiation, the genomes of Darwin’s finches were re-sequenced in 2015 by researchers led by Peter and Rosemary Grant, along with colleagues from Uppsala University (Lamichhaney et al. 2015). The group then used admixture mapping to determine whether the finch traits were heritable, and if so which parts of the genome were responsible (Rubin et al. 2022). Interestingly, their work allowed them to report that the genetic variation underlying the finch beak changes had pre-existed in the population:

We show that the origin of these haplotype blocks linked to phenotypic divergence predates speciation events. (Rubin et al. 2022)

In other words, these scientists discovered that haplotype blocks, sections of DNA at recombination cold-spots, existed before the finch radiation. Because the blocks are within recombination cold-spots, this is thought to have allowed persistence of the loci traveling together in spite of gene flow between populations. The authors note that when the genetic variation pre-exists in the population, then adaptation can happen quickly.

While rapid speciation in adaptive radiations provides limited time to generate de novo genetic variation, ancestral polymorphisms can facilitate rapid accumulation of diverse combinations of alleles. (Rubin et al. 2022)

The crucial point here is that random accumulating mutation did not lead to the radiation. Instead, finch adaptation that moved along a pareto front was driven by pre-existing genetic variation.

Traits and Genetics

The unique finch traits and the genetics underlying them are not positively correlated. Instead, they are negatively correlated. This means the alleles underlying the adaptation are linked to trade-offs, for example the trade-off between being optimized for big seeds versus being optimized for small seeds. Rare random mutations lead to positive correlations, but the alleles underlying these traits are linked to trade-offs or negative correlations. This further supports the observation that genetic potential is built into the finch population, connected, again, with the concept of trade-offs.

We see that, in the most classic example of “evolution happening before our eyes,” genetic variation was present before the adaptive radiation. Whether this is truly “evolution” is, then, a question worth discussing.

Sources

- Alon, Uri. 2019. An Introduction to Systems Biology: Design Principles of Biological Circuits. Second edition. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press, [2019]: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Grant, Peter R., and B. Rosemary Grant. 2002. “Unpredictable Evolution in a 30-Year Study of Darwin’s Finches.” Science, April. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1070315.

- Lamichhaney, Sangeet, Jonas Berglund, Markus Sällman Almén, Khurram Maqbool, Manfred Grabherr, Alvaro Martinez-Barrio, Marta Promerová, et al. 2015. “Evolution of Darwin’s Finches and Their Beaks Revealed by Genome Sequencing.” Nature 518 (7539): 371–75.

- Rubin, Carl-Johan, Erik D. Enbody, Mariya P. Dobreva, Arhat Abzhanov, Brian W. Davis, Sangeet Lamichhaney, Mats Pettersson, et al. 2022. “Rapid Adaptive Radiation of Darwin’s Finches Depends on Ancestral Genetic Modules.” Science Advances 8 (27): eabm5982.

- Shoval, O., H. Sheftel, G. Shinar, Y. Hart, O. Ramote, A. Mayo, E. Dekel, K. Kavanagh, and U. Alon. 2012. “Evolutionary Trade-Offs, Pareto Optimality, and the Geometry of Phenotype Space.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 336 (6085): 1157–60.