Fantastic Voyage is the title of a 1966 science fiction film about — well, if you don’t remember what it’s about, I won’t spoil this by our colleague Jonathan Witt who imagines another “fantastic voyage” in the current issue of Salvo Magazine to help explain the idea of intelligent design:

A Scientific Odyssey

Did mind make matter, or matter mind? Are the things of nature the product of mindless forces alone, or did creative reason play a role? Theologians have grappled with the question but so have philosophers and scientists stretching from ancient Athens to modern Nobel Prize winners.

In 1859, Charles Darwin introduced his theory of evolution to argue that blind nature had produced all the species of plants and animals around us. The new theory convinced a lot of people that evidence of a Creator could not be found in nature, and indeed, should not be sought. If there are things in nature that remain mysterious, the thinking went, scientists will figure them out in time. To attribute their origin to God was simply to give up on science.

Today, Darwinists level the same charge against the contemporary theory of intelligent design (ID). They insist that ID is just an argument from ignorance — plugging God into the gaps of our current scientific understanding. Darwinists have made many thoughtful arguments over the years, but this isn’t one of them. The theory of intelligent design holds that many things in nature carry a clear signature of design. The theory isn’t based on what scientists don’t know about nature, but on what they do know. It’s built on a host of scientific discoveries. To demonstrate, let’s take a journey.

Miracle of Rare Device

You’re a computer geek living thirty years in the future, and you just won a lottery for a space flight to a distant planet, as yet unnamed. The rendezvous is SpaceX in south Texas. After a thorough physical, you enter the raindrop-shaped vessel along with the captain, pilot, and two other lottery winners. You’re strapped into a cockpit with a panoramic window and hooked to various wires, patches, and tubes. The lottery winner to your left is a burly submarine engineer with short-cropped salt-and-pepper hair. The lottery winner to your right is a gangly blonde in her early thirties, a Caltech physicist.

The hatch is shut. The countdown begins. At seven you hear a low groaning. At three it drops an octave, the lights flicker, and your teeth vibrate inside your gums. At zero the cabin falls silent, a stab of pain runs the length of your body, and you fall into darkness.

When you wake, eyes blurry, head aching, you rub your eyes and see that the ship is already approaching a moon marked by a pattern of blobs haphazardly swinging this way and that over the surface. How long were you asleep?

As your ship draws closer, you realize the moon isn’t like any moon you’ve ever heard about. Your hands are clenched on the armrests. You try to relax. Farther and farther the ship descends. It’s clear now that this strange moon is closer and smaller than you supposed, maybe only a dozen miles away and as many across.

If it’s just a big asteroid, it’s a strange one — almost perfectly round.

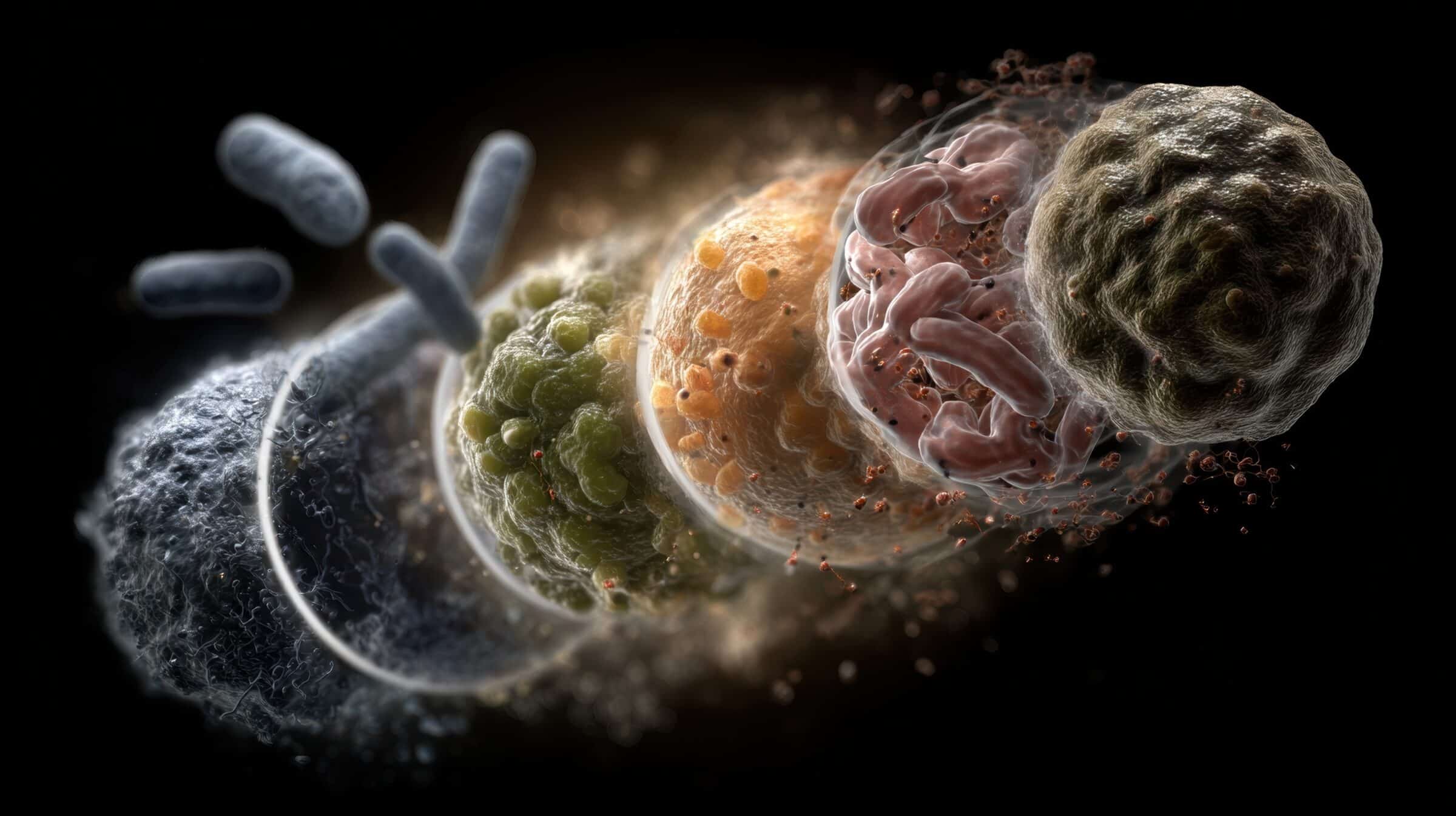

Suddenly you realize, it’s not a moon. It’s a giant machine, one far bigger than any manmade object you’ve ever encountered.

You’re close enough now to make out millions of portholes on its surface, portholes opening and shutting as millions of ships enter and exit.

You expect your ship to move into orbit around the space station, but now you realize that one hole — barely larger than the ship — lies directly ahead and the pilot is making straight for it.

An intriguing premise, don’t you think? Read the rest at Salvo. The article is adapted from Dr. Witt’s book with Dr. William Dembski, Intelligent Design Uncensored: An Easy-to-Understand Guide to the Controversy (InterVarsity Press).