A 2020 paper published high-resolution images of centrioles that showcase their structural organization: complete with stacks of cartwheel-shaped frameworks, struts, and linkers. It’s hard to look at the models and not infer design.

Centrioles are microtubule organizing centers. The barrel-shaped structures with radial symmetry, often appearing in mother-daughter pairs positioned at right angles, play important roles in eukaryotic animal cells both during and between cell divisions. During interphase, they form the basal bodies of cilia and flagella, directing the construction of microtubules into those motile organelles. During cell division, they direct the construction of the mitotic spindle that winches sister chromatids apart into the daughter cells. Though present in some lower plants, centrioles are missing in oocytes, conifers, and flowering plants.1

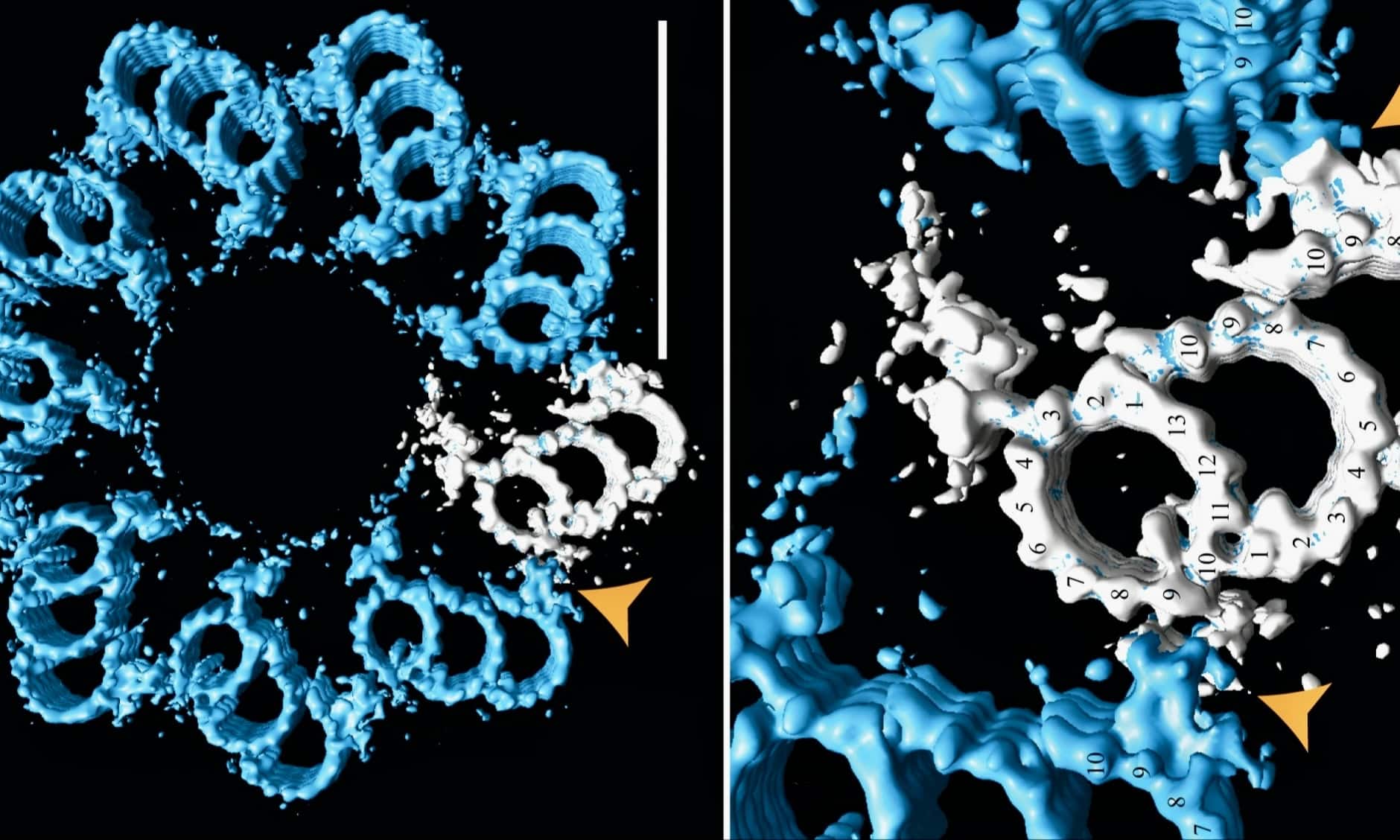

Of all the organelles in a cell, centrioles stick out in electron micrographs like miniature icons of design, appearing as cylinders lengthwise or like tiny 9-petaled flowers end-on. An open-access paper in The EMBO Journal revealed structural details of the “cartwheel-containing region” of a centriole using cryo-electron tomography.2 Readers should browse the image sets to glimpse the beauty and complexity of these stacked “cartwheels” that hold the nine triplets of microtubules in radial position 40° apart like stacked wheels with 9 spokes. Multiple proteins link up at each segment and then continue upward to form the architecturally precise centriole. This shows there are many more parts involved than pictured in this simplified model at ThoughtCo or this marginal animation at Microscopic Galaxy.

Darwinian Gobbledygook

Notably, the 15 authors of the paper speak of these structures as “evolutionarily conserved” (Darwinian gobbledygook for un-evolved) between protists and humans. A few variations exist but for the most part they follow the same pattern and function.

Normally residing near the nucleus during interphase, the orthogonal pairs of centrioles constitute what is known as the centrosome, which recruits over a dozen other proteins called pericentriolar material (PCM). The “cartwheels” do not rotate or perform motor-like actions themselves.3 Rather, the centrioles migrate where needed. At cilia or flagella, they direct the construction of microtubules at those sites, undergoing modifications to become what are called basal bodies. Basal bodies direct the construction of the axoneme where machines build a cilium or flagellum from the inside out using an internal motorized transportation system called intra-flagellar transport (IFT).

Centrioles in Mitosis

Centrioles take center stage in mitosis. In prophase, the centrioles duplicate into a second pair by a carefully orchestrated process involving multiple proteins. The two pairs migrate to opposite poles of the cell while the chromosomes pair up. From the poles, the centrioles assisted by the PCM in the centrosomes produce “asters” of microtubules that grow toward the chromosome. The chromosomes, now in pairs, perform congression, or lineup, along the cell’s central axis. During metaphase, the spindle fibers are guided to attachments at kinetochores (“movement places”) located at the centers of the chromosomes. When all the components have passed the spindle assembly checkpoint, motor proteins (kinesins) shorten the microtubules, pulling the sister chromatids apart into the daughter cells. Then cytokinesis begins. A contractile ring cinches the outer membrane down the center using actin and myosin motor proteins. The result: two identical cells.

We learned the basics of mitosis in high school (below is a review animation from North Dakota State University). But as with most things in biology, the complexity expands the closer you look. Numerous protein machines assist at every step. The orderly and rapid process of DNA replication, for instance, is a true wonder of nature. It’s like robotic machinery duplicating a car, part by part, while it is moving through traffic, and ending up with two moving vehicles!

Complexity Overload

Had enough specified complexity yet? There’s more. Now in Nature Communications, Kruno Vukušić and Iva M. Tolić from the Division of Molecular Biology at the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Croatia have published two papers about signaling and coordination of protein machines during mitosis.4, 5 For fun, have a taste of the elements involved and picture this as a football announcer listing players while trying to figure out the quarterback’s strategy:

While our study highlights the central role of CENP-E and Aurora kinases in chromosome congression, other spindle-associated proteins are likely involved. HURP and CLASP proteins, for instance, stabilize and regulate kinetochore microtubules near chromosomes, and the Ska complex enhances kinetochore–microtubule coupling under tension. At the spindle poles and in their vicinity, factors such as TPX2, pericentriolar proteins, kinesin-13 depolymerases, the crosslinker NuMA, and the Augmin complex are all intricately linked to Aurora A signaling. These pathways may act downstream of CENP-E and Aurora kinases to influence both congression efficiency and spatial bias, meriting further investigation. [Emphasis added.]

Don’t worry; these won’t be on the quiz. So many protein parts! Every one of them appears at the right place, at the right time, knowing exactly what to do.

What about those centrioles? The authors mention them 120 times in one paper and half a dozen times in the other. Surprisingly, cell division can proceed even in the absence of centrioles:

Our findings suggest that it is not the presence of centrioles per se, but rather elevated Aurora A kinase activity that governs the feedback dynamics between spindle poles and kinetochores. In somatic cells, Aurora A activity is associated with canonical centrosomes [i.e., those with centrioles], whereas oocytes maintain Aurora A activity and form functional spindles without canonical centrosomes. This may explain why oocytes, but not acentriolar poles in somatic cells, require CENP-E for chromosome congression despite the absence of centrioles. We propose that kinetochore feedback mechanisms controlled by Aurora A may operate independently of centrioles, highlighting the need for further study of chromosome congression regulation in acentriolar contexts.

Centrioles, the authors show, are parts of a broader communication network that can respond to a variety of conditions. Two kinases (proteins that phosphorylate other molecules) called Aurora A and B are key regulators; Aurora A works in the centrosome, and Aurora B at the kinetochore, but they respond to each other and to other signals. Centrioles can inhibit congression in the absence of another key component named CENP-E, a kinesin motor protein involved in congression. “The findings overturn two decades of textbook understanding and carry major implications for life sciences,” a writeup on Phys.org states.

Under normal conditions, CENP-E acts like a foreman, ensuring that each chromosome on the lineup is securely attached to its microtubule, taut, and ready for motion. If so, it contributes to the spindle assembly checkpoint, making the next level administrator, BUBR1, know that all systems are go for anaphase. (See my cowboy analogy here.)

The researchers tried removing the centrioles to see what would happen. Congression could still occur, but spindles were misshapen and asymmetrical. Playing with various scenarios, they figured that a “larger signaling network” than previously thought was involved.

Our study demonstrates that centrosomes inhibit congression initiation when CENP-E is inactive by regulating the activity of kinetochore components. Depletion of centrioles via Plk4 kinase inhibition allows chromosomes near acentriolar poles to initiate congression independently of CENP-E. At centriolar poles, high Aurora A kinase enhances Aurora B activity, increasing phosphorylation of microtubule-binding proteins at kinetochores and preventing stable microtubule attachments in the absence of CENP-E. Conversely, inhibition of Aurora A or expression of a dephosphorylatable mutant of the kinetochore microtubule-binding protein Hec1 enables congression initiation without CENP-E. We propose a negative feedback mechanism involving Aurora kinases and CENP-E that regulates the timing of chromosome movement by modulating kinetochore–microtubule attachments and fibrous corona expansion, with the Aurora A activity gradient providing critical spatial cues for the network’s function.

While parts of metaphase can proceed if one part or another is missing, no protein is superfluous. Think of an orchestra conductor deciding if the concert can go on if the bassoon player is missing. Depending on the program, he might ask the bass clarinet to read the bassoon cue notes. That is a weak analogy, but it illustrates how cells can evaluate a multitude of factors to make go/no-go situations. Consider the foresight involved in having multiple “checkpoints” at different stages of cell division. The authors are not even sure they have figured it all out. “These seemingly paradoxical activities of Aurora kinases within the same process,” they confess, “suggest a signaling feedback loop among mitotic spindle components, the nature and regulation of which remain unknown.”

The Degree of Coordination

My purpose here is not to overwhelm readers with details, but to use the details to emphasize the degree of coordination involved in cell biology. What may have looked to us high school students like a simple process (“Oh, look,” a student might say viewing mitosis through a light microscope, “the chromosomes are being pulled apart!”) turns out to be enormously complex. The complexity is not messy, despite dozens of players going this way and that: it is specified complexity — structural complexity — functional complexity, yielding near perfect results over the entire biosphere for uncountable quintillions of mitotic operations. That Phys.org article cited above agrees:

Every second, trillions of times over, your body pulls off something that’s nothing short of miraculous. A single cell prepares to divide, carrying three billion letters of DNA, and somehow ensures both daughter cells receive perfect copies.

“Nothing short of miraculous,” they say. Let us never underestimate the degree of design in biology. I often think about the fact that, until our generation (now that scientists can image these processes at the nanometer scale), humans throughout history had only vague notions of the degree of sophistication at the basis of life within and around them. Cell theory was not even established until the mid-19th century. Maybe in Darwin’s day scientists could imagine cells assembling in warm little ponds by chance, but that option is no longer credible. Today there is no excuse for not embracing intelligent design.

Notes

- Is the lack of centrioles in higher plants a case of evolutionary loss? I’ll leave that for others to contemplate, but the presence of rigid cell walls may eliminate the need for centrioles. Instead, higher plants use diffuse MTOC (microtubule organizing centers) and other structures to guide their spindle fibers into position.

- Klena et al., Architecture of the centriole cartwheel‐containing region revealed by cryo‐electron tomography. The Embo Journal, EMBO J (2020) 39: e106246.

- Unfortunately, I could not find any support for Jonathan Wells’s creative “turbine hypothesis” for centrioles from 2011, but much is still unknown. See his 2008 article.

- Vukušić and Tolić, Kinetochore-centrosome feedback linking CENP-E and Aurora kinases controls chromosome congression. Nature Communications 16, 9097 (2025).

- Vukušić and Tolić, CENP-E initiates chromosome congression by opposing Aurora kinases to promote end-on attachments. Nature Communications volume 16, 8537 (2025).